Zicky and Moshe had teamed up for a full-court press. “Listen, Barry,” they badgered me one Shabbat evening: “You’re graduating soon from the Seminary, right? Headed to a congregation, right? Wisconsin Ramah is the movement’s crown jewel, right? Then, how can you NOT spend a summer there on staff!”

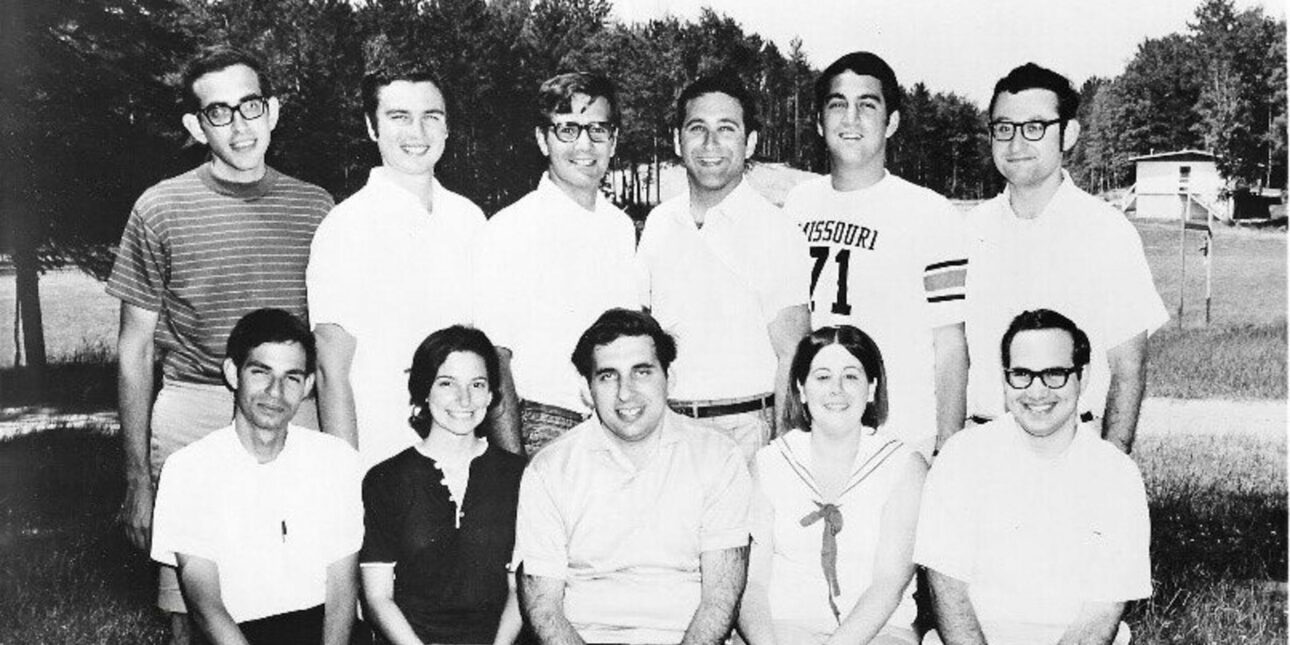

I had grown up in the Zionist youth movement and had worked almost every summer at one of that era’s Young Judaea camps. But the logic of my two JTS mates was irrefutable. They arranged an interview with Rabbi Cohen [he would become “Burt” only months later], and apparently, it went well enough. I was invited onto the staff, alongside many other fellow JTS friends, and with one of my favorite professors, Rabbi Francus, as well.

Weeks before the camp was to open, Burt phoned from Chicago. “We’ve got a slight problem. A good one. More registration for the Machon than projected! It would be good to add some experienced staff support. I’ve got just the person to be S’ganit Rosh. Her name is Phyllis Weinstein. She was a counselor last summer but had planned to work at her synagogue’s day camp this year. The congregation is building a new campus and had to cancel. She’s thinking of returning.”

This coming fall, Phyllis and I will be celebrating our 50th wedding anniversary. And one of the ways we intend to thank Burt Cohen and Ramah for arranging our shidduch is by making a legacy gift. This past fall, when we were with Chicago family for Thanksgiving, HaRav Soloff and I had a chance to speak. It was a gratifying meeting, hearing about the prodigious plans camp leadership has developed, including the crucial role envisioned for the camp’s endowment.

David’s words about the consequence of endowed giving sparked a memory of my days at the Adath. So much so that when I returned to the Twin Cities, I set about learning what had happened to the gift of Leon Finkelstein.

I had met Leon when serving as the rabbi at the synagogue. Leon and his sister Ida had been raised in an upper-middle-class Jewish household in Hamburg, Germany. As hatred took over their 1930’s homeland, their parents sought refuge for their children. Brother and sister were among the 17,000 refugees safely ferried to Shanghai. After the war, they made their way to Minnesota.

“My sister died shortly before you came to the synagogue,” Leon told me one afternoon. “And now, I fear for what will happen to my life’s savings after I am gone. Will you be the executor of our estate?” After Leon’s death, a congregant lawyer friend and I packed up his possessions, and discharged the directions of his will. Some modest amounts were allocated to local social service agencies. The rest went to the University of Minnesota, directed to scholarships for recent arrivals to these shores.

My curiosity was unexpectedly awakened by that conversation in Chicago, I called the U’s advancement office. Recounting my connection to Leon, I inquired if they could share the chronicle of his bequest.

Through astute investments, that fund has more than doubled, the planning officer disclosed, while simultaneously distributing some 80 scholarships to first-generation college students. Her words bowled me over. The trust Leon vested in the University had been honored; students had been, and will continue to be supported, beyond measure; and a precious family name has been kept alive.

In an era requiring ever-increasing private resources to sustain superior education and vibrant communal life, the legacy fund at Camp Ramah, as those at so many of our colleges and universities, has an ever-increasing central role. Leon’s story brought that to life for Phyllis and me in a way we might never have imagined. It’s an honor to join so many alumni, colleagues and fellow supporters in this important work at Machaneh Ramah.

Rabbi Barry Cytron

Zicky was Rabbi Isaac Bonder, z”l, for whom Ohel Yitzchak is named. Moshe is, of course, Rabbi Moshe Rothblum, the renowned Rosh Drama at camp.