Please enjoy a d’var Torah this week from Jon Adam Ross (JAR). JAR is the Managing Director of The In[HEIR]itance Project, an organization which practices an open artistic process to create theater from authentic community dialogue about shared inheritances. JAR has spent nearly 20 years making art with religious communities around the country as an actor, playwright, and teaching artist. He has served as an artist in residence at Union Theological Seminary, The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, and many other religious and educational institutions. JAR was a Spielberg Fellow in Jewish Theater Education with the Foundation for Jewish Camp and has spent 20 summers on staff at Camp Ramah in Wisconsin. As an actor, JAR has performed in over 90 cities around the globe. His stage credits include: a dog, a 2,000 year old bird, an elderly orthodox Jew, a spurned housewife, a horse, a British naval officer in 1700’s Jamaica, a goat, Jesus, a lawyer, a hapless police chief, and a cyclops. JAR holds a BFA in Acting from NYU/Tisch.

Protest: Reflections on Parashat Korach

by Jon Adam Ross

I remember the first time I heard Korach’s name. I was a camper in Bogrim. And while I’m sure I’d heard about Korach in the prior summers at camp, this was the first time I’d really HEARD his name. Korach: the rebel. Korach: the bitter. Korach: the ungrateful. Wasn’t liberation enough for him? Wasn’t freedom? And food? And the promise of a better future in the ‘promised land’? This was 1995 and I had no clue. From 1980, the year I was born, until then, there hadn’t been any marches in my neighborhood in the suburbs of Memphis. I’d never experienced protest, not for real. On TV, sure; clips of the early 60’s and the fight for civil rights; clips from from the late 60’s and the fight against Vietnam. Forrest Gump came out the previous July. It was NOT the movie we saw on our Shoafim yitziyah (day trip). I had to wait until I got back to Memphis and then beg my parents to let me see it. And even then, the protests were just a passing scene. All of this is to say, I had no context for understanding the complicated relationship our inherited Judaism has with the concept of protest.

This week’s parashah begs us to confront that legacy, so let’s do just that. Korach’s rebellion is judged harshly by God and the Torah. He was a spoiled brat, a member of the 1% who wanted more. And his message wasn’t populist, it was elitist. I understand the disdain Judaism has for Korach’s intentions. But can we talk about Korach’s methods for a moment? I want to lay out a comparison: Person A is wealthy, a member of the elite. He has a desire to challenge the ruling power structure, and does so with words, challenging conversation, and ritual offering. Person B is wealthy, a member of the elite. He has a desire to challenge the ruling power structure, and does so by committing murder, running from the authorities, and then leading an uprising that results in property damage, plague, and, eventually, the massacre of children. Who’s the hero of this story? According to this week’s parsha, it’s Person B, who foils Person A’s rebellion with help from God who kills all the rebels with one earthquake.

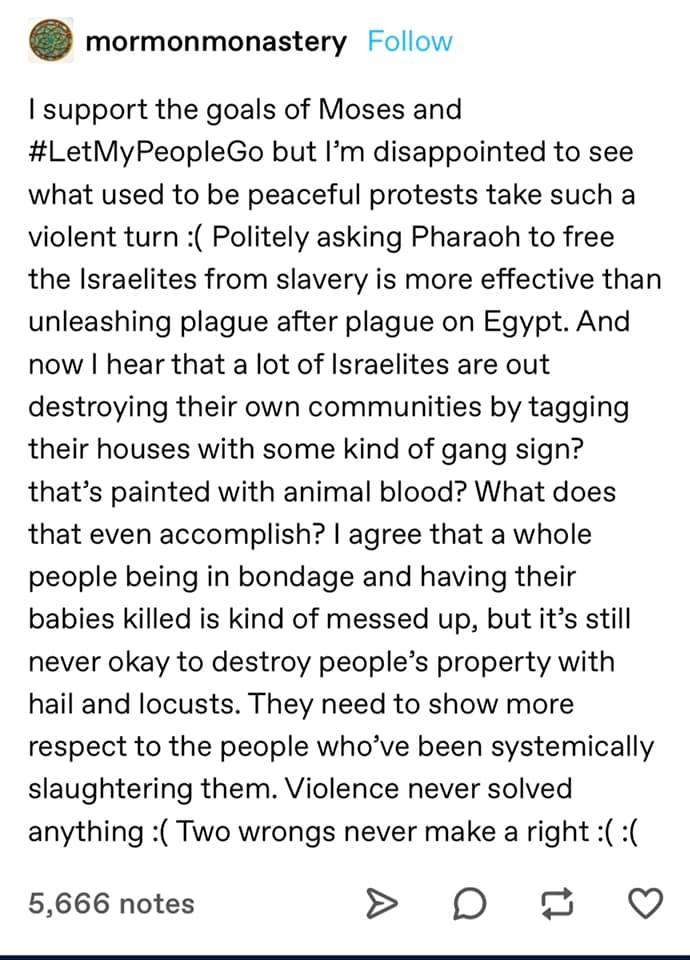

This post came across my news feed last week. Was Moses a leader of a protest movement? It had never occurred to me to think of him that way. Were his methodologies inappropriately violent? Again, news to me. And it got me thinking: what is the role of protest in Judaism? And where is the line that defines what actions in the name of change are moral or immoral? I want to stay out of the 20th and 21st centuries for this discussion: we’re too close to those times, and too sensitive as well. But clearly the Torah is stating here that for the right reasons, violent rebellion is justified. And for the wrong reasons, peaceful rebellion is punishable by death.But there’s more. There’s also rebellion through art in the Torah. Remember the Golden Calf? The perpetrators of that ritual protest were also punished with death. So protest in the name of God is kosher, but protest against God is not. That seems to be the clear barometer in the Torah. So looking, now, at today, how do we know which protests are in the name of God and which are against God? And who gets to make that call? The Rabbis marching for Black lives? Or the Rabbis defying local ordinances by holding ritual gatherings that flout COVID restrictions? There is a midrash (Babylonian Talmud, Megillah 10b and Sanhedrin 39b) that tells of the angels on high celebrating in song after the pursuing Egyptian army is drowned in the Red Sea. Per the midrash, God responds, “מעשה ידי טובעין בים ואתם אומרים שירה לפני” (“The work of my hands drowns in the sea and you are singing about it in front of me?!”). Clearly, our sages take the stance in this moment that, like Adam, all people are created b’tzelem elohim – in God’s image. But then why the double standard? God weeps for the soldiers here but not a peep about makat bechorot (death of the firstborn)?

I’ve thought a lot about this over the past few weeks, about the messages our shared, inherited texts are sending about protest. Dr. Ethan Schwartz (Nivo ‘06) taught a fascinating shiur (text study) on Shabbat in 2018 about Korach that presented counter-cultural views in Jewish wisdom related to Korach’s counter-cultural movement. And in 2019, Rabbi Jane Kanarek taught a shiur about a different rebellion, one that I haven’t mentioned yet: the rebellion of the women. Way before Moses killed that slavemaster, the midwives had already executed their own plan of resistance, refusing to slaughter the Hebrew baby boys. The wives of the men toiling in the fields had already broken rules against slave procreation by bringing food and warmth to their husbands in secret. And a mother, saving her son from a death sentence, had already given her baby up to the tides, placing him in a basket with a prayer for salvation.

It’s 2020. A pandemic is exploiting the broken systems of our present and a reckoning with our inherited history of prejudice is reshaping our future. People are upset, and their voices are raised in protest: they chant as they march in the streets, they yell out on social media, they write op-eds in the paper and sermons for their congregations. People are upset, and they act out in protest with violence: they destroy property, they steal, or they willingly walk in a store without a mask in violation of the store rules, not caring who might get sick or die from their maskless action. Confused about which form of protest is right and which way is wrong? So is our tradition. And so am I.